Claire Wellesley-Smith

Claire Wellesley-Smith focuses on long term, community-based work. Find out about her practice and her journey as a textile artist.

Claire’s Friday Feature Artist Interview can be found at the bottom of this page.

Claire Wellesley-Smith’s practice is focused on long-term, community-based work, often spanning several years and overlapping multiple projects at one time, the effects of which can be life-changing for the participants.

Living in Bradford, West Yorkshire, surrounded by a rich heritage of the textile, trade and manufacturing era of the 19th century, particularly wool and cotton, offers an abundance of inspiration for Claire’s archival research and textile-based projects, including planting dye gardens and teaching students how to create their own colour.

Claire’s project work and wonderful books offer the opportunity to ask questions and consider the implications of our modern relationship with textiles. Fibre Arts Take Two was lucky enough to talk with Claire and discover more about her passions.

Textile people

Textiles were part of Claire’s life from the very beginning, “I grew up in a household where my mother and grandmother were extremely skilled textile people. My mother can make clothes; she knits, crochets, she embroiders. She’s very, very skilled, as well as my grandmother. I grew up in an environment where people were always making things, always mending.”

Despite her early involvement with textiles, Claire says her journey to fibre arts was anything but straightforward, “I went to university and studied politics, but I lived in a house full of fine art students, so we had a communal rag back for making clothes and mending things. There was always a kind of making element to everyday life for me. But regarding how I got into textile practice, that happened after a brief time working in community engagement around higher education. I was facilitating people who had barriers to participating in education, back into education and doing a lot of textile work in my spare time. I eventually went to night school to do some creative textile courses. That work led to volunteering, which then led to more formal project-based stuff.”

The urban environment

Over the last 12 years, a lot of Claire’s projects have been based in urban environments,

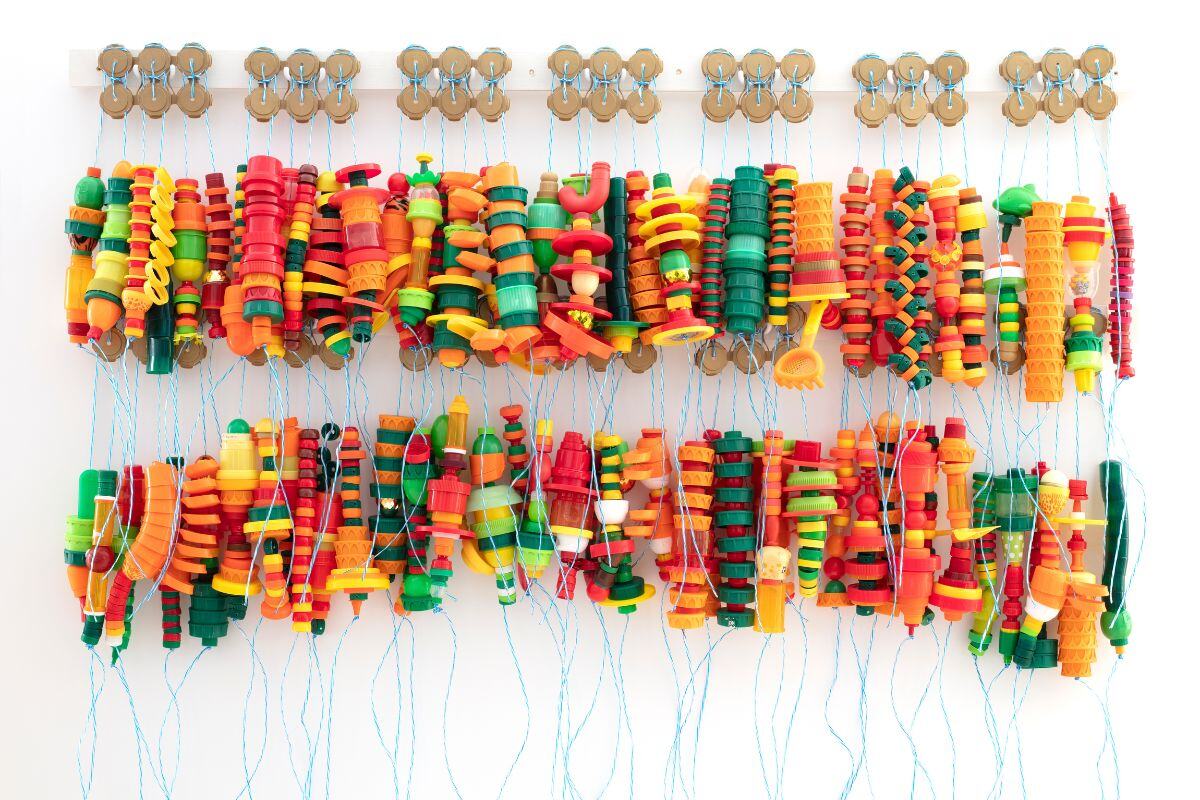

“They’ve been developed in non-garden spaces, and they’ve spoken about mental health and connections to heritage. They’ve popped up at community centres… we had a garden in a car park. We were not working with big formal spaces; we borrowed bits of community allotments and things like that. I love these projects because there’s this whole process of growing something, nurturing it, working together to achieve it, and then being able to work in a really seasonal way.”

In Northern England, the seasons have a way of dictating life. “Autumn and winter are quite cold, and it’s definitely not the growing season. During those months, we work with the materials we’ve dyed and work together on collected projects and create the space for people to have conversations while making things.”

Worn Stories

Claire’s collaboration, Worn Stories, is a perfect example of how her collaborations embrace community and history.

Bradford, where Claire practices, has a textile industry dating back hundreds of years. “The project really addressed the history of textile recycling, reuse and repair in the community from the 1880s onwards. We offered an opportunity to think about contemporary textile practices and how we consume textiles by looking at the histories of businesses and workers who were engaged in textile recycling. It involved archived research; participants learned research skills, and they accessed archives. They were able to tell the stories of some of the women in that industry.”

Fast fashion

Being based in a textile town and working with fibre materials has Claire thinking about the state of the fashion and textile industry and the danger of fast fashion, “I think that a huge thing in terms of how people consume stuff is they don’t think about how things are made. They don’t think about who’s making them because you must look a bit further to see it. Making those kinds of supply chains more visible could be really important and make people think about the reality of a T-shirt that costs two pounds or two dollars. What is that saying about the people making this and where it’s coming from?”

Claire sees hope, though, in the form of individuality and creativity, “I’ve got four daughters, and I’ve noticed they’re consuming habits starting to change, actually. They’ve had part-time jobs and a bit of spending power for the first time in their lives. To begin with, there were parcels arriving all the time from some really dubious manufacturers, and I had to hold my tongue a little bit. Still, one of the things definitely emerged is that they’re starting to think about how they can look, you know, like themselves, and that they have some sort of individuality. One of the things about these collections of very fast fashion is the uniformity and the fact that everybody is wearing very similar things. My 19-year-old just got a sewing machine now in her room. She’s chopping up and altering things and making new things out of old things, and she buys second-hand and then alters it. I think more examples of that do make a big difference. I like that you can make things that are just for you.”

Transitions

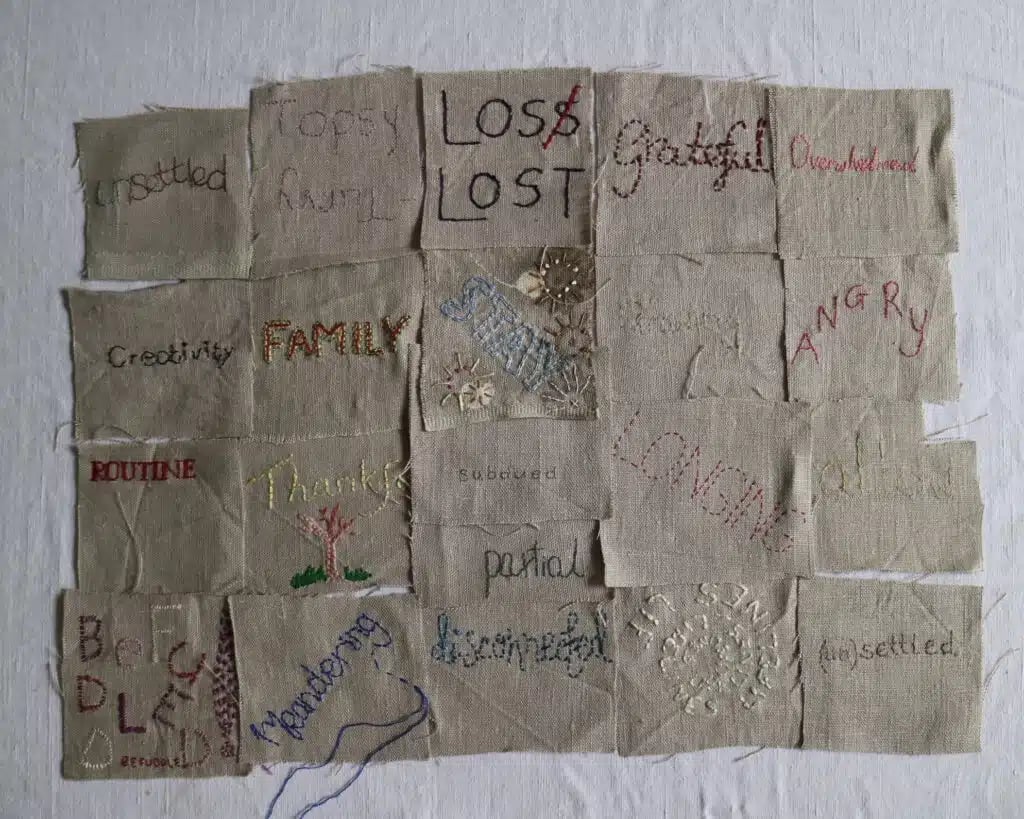

Being a community-based artist has had its challenges over the past 12 months or so,

“Those sorts of community projects, just in terms of face-to-face work, were impossible at all. I mean, we have had breaks in the lockdown, but in the north of England, we had very few periods where we weren’t in some sort of lockdown, either national or local restrictions.

A lot of my work is with organisations that work with adults who might be experiencing some sort of social isolation. That could be due to long-term health conditions; it could be due to bereavement; it could be due to issues around substance abuse; there are lots and lots of things. That means that many of the people who participate in my projects would be vulnerable groups anyway. The kind of opportunity for them to come out to meet up would have been very difficult anyway, so there’s been a big kind of pivot to online work.”

While online work has been essential, Claire remains keenly aware of some of its shortcomings, “You have to appreciate that digital exclusion is something that also exists. Not everybody has the skills, and not everybody has access to high-quality broadband or any broadband in some cases. So there most definitely is a group of people who have been completely excluded despite the best efforts of community organisations to get them online and get that access going.

It’s been really interesting as somebody who’s worked with people in a face-to-face way for so long. It’s challenged me. I’ve had to really think about how I do things. I’ve had to skill myself up in various ways in terms of technology, and I’ve had to recognise that online spaces are brilliant.”

Make it meaningful

“Make it meaningful for you. I think that’s the thing,” says Claire as her parting advice to aspiring artists, “That could be through the colours that you stitch with, it could be through the fabrics you choose to use, but make that connection and make it for you. And I think that’s a really nice way to work because it doesn’t have to be for anyone else, and you will understand why it’s important to you.”

About the artist

Claire Wellesley-Smith is an artist, writer and researcher based in Bradford, West Yorkshire. She studied politics as an undergraduate at Newcastle University and has a Masters degree in Visual Arts from Bradford School of Art. She is currently a doctoral candidate at the Open University, researching slow craft practices and engagement with personal and community heritage. She specialises in projects that use local, natural colours created from home-grown and locally foraged plants. Dyes and stitches on reclaimed cloth are used in slow processes that allow time to consider production methods and narratives of use. Claire uses archival research as the starting point for her work, looking at locations and community stories. Cloth, dye and stitch are then used as carriers of the natural and social history of the place.

Socially-engaged arts projects are a key part of Claire’s practice. Her projects are often long-term community-based engagements and explore how place, heritage and memory can connect people to their surrounding environment.

Notifications

Join Our Newsletter

OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

View our interviews and more on our Youtube channel!

OUR FACEBOOK GROUP

Join our Community and stay updated with our upcoming announcements!